This conversation was the kick-off for a new Rand/YSN collaboration that combines YSN’s adaptive tools for youth career planning and global youth experience with Rand’s analysis expertise and policy orientation, with a goal of building an evidence-based guide to youth workforce readiness.

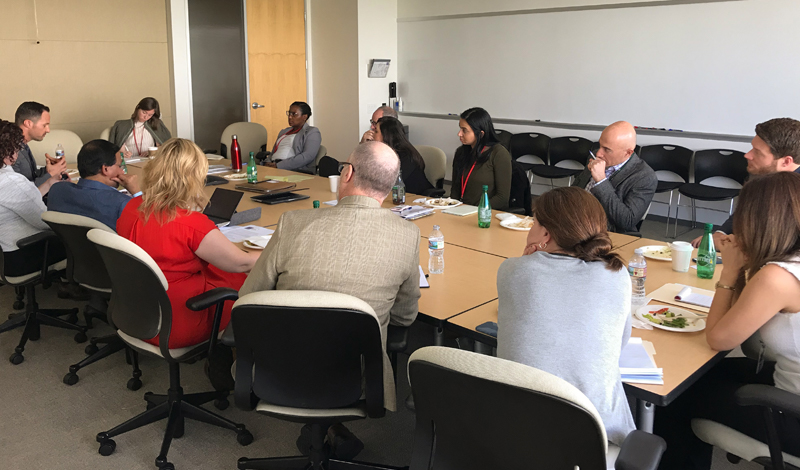

The session was held at RAND in Santa Monica. It was moderated by:

Krishna B. Kumar

RAND Senior Economist & Director of the Labor and Population Unit

Distinguished Chair in International Economic Policy

Professor, Pardee RAND Graduate School

Darlene Opfer

Director, RAND Education

Distinguished Chair in Education Policy

Former Director of Research University of Cambridge

Jennifer Kushell

CEO & Founder, YSN

Creator of Exploring Your Potential™

NY Times Bestselling Author, Secrets of the Young & Successful

In a room filled with forward-thinking, dedicated career professionals—as well as business leaders who have returned to academia—the casual, intimate discussion touched on what is and isn’t happening in terms of the education-workforce pipeline, and what factors come most into play.

Today’s student populations.

- California universities talked a lot about the diversity of their populations, the large numbers of first-generation students, and also of some of the challenges they face coming from underserved and low-income communities and families.

- At CSULA, 80% of their students are first generation and 60% are Latino.

- The anxiety that students face, overall, is incredible.

Family involvement.

- Affluent families are often over-involved in guiding their children into particular majors and professions, with a focus on starting salary and benefits. This makes it harder for students to choose their own path and complicates how “coachable” students are by the university counselors who are trying to help them navigate their options.

- Less economically secure families tend to be far less involved in the student’s education and career choices. In addition, students from these families usually have much higher levels of responsibility as they often help support their families while in school, juggling work or a family business while trying to complete their education.

- Lower income students tend to expect less support on campus—but when they are engaged, school counselors can often guide them much more effectively as they have less family pressure toward a certain career.

- Today’s college students will change careers about twelve times in their lifetime, but most of them are not ready to hear this or understand what today’s world of work is like because—especially with first generation students—all they can think about is the urgency of getting a degree and getting a job to support their families.

Demand for traditional jobs is shrinking.

- “The Workforce of the future, it is changing,” warned Krishna Kumar, Director of Labor and Population at RAND. “One of the more famous surveys that was done on the RAND American Life Panel…over the past dozen or so years, finds that there is a huge increase just in the last ten years of people who do contract work.” Clearly this is a huge trend among students and recent graduates. More and more they’re looking for flexible work vs. more traditional positions with established firms. “How can the education sector change in response to the labor market?”

- Darlene Opfer, who directs Education at RAND added, “we’ve done a number of studies in different regions of the country…looking at where the jobs are and in what fields, then looking at what kinds of programs are being offered. And we regularly see that the programs are not matching the jobs. How do we get institutions to respond and open up to new programs when there’s clearly a labor market need?”

The pace of change makes it almost impossible to keep up.

- The pace of change of the workforce itself is a big issue. It used to take generations for changes in technology to impact what jobs are needed; now it takes years. This makes it harder for schools to teach what is needed. Sloan Trugman, a consultant to YSN, said, “There’s a big gap between the institution and employers and unfortunately students suffer [the most].”

- Bob Sheridan who heads Career Education/Professional Development at the David Nazarian College of Business and Economics at CSUN pointed out that most of his students take six years to graduate because they are also working to support their families. With today’s rate of change in the workforce, no one—including VPs at IBM, whom Sheridan visited with this question—can see six years into the future to know what skills or tech will be needed, particularly with STEM. So there is no way for schools or teachers to know what to teach.

- Sheridan’s solution to this is to focus on teaching how to learn rather than on specific skills. His course called Themes and Structures of Lifelong Learning covers critical thinking, persuasion, execution, situational analysis, cultural and global awareness, and—most importantly—technical and scientific conversations.

- Kumar added, “If we can figure out what it is that individuals are going to need 5, 10, years from now, even if it’s opaque….10 years ago we didn’t have our iPhones, but we now use that piece of technology to manipulate information. So, we don’t know what the next iPhone is, but we know you need to be able to manipulate information. See where it fits. How data interacts with one another. That is probably doing to be one of the more transferable skills – sort of like the conceptual underpinning.

Students don’t understand today’s work world—and many administrators are struggling to keep up, too.

- Kushell’s work at YSN has brought her around the world, working with tens of thousands of students as they struggle with their own personal identification and career exploration.

- Globally, she sees a lack of engagement with on-campus career resources as students don’t see what’s being taught as relevant to their lives and interests. Career readiness in college often focuses on resumes or on programs that encourage students to connect directly with employers, when the real issue is that students don’t know who they are, what skills they have, or how those skills translate into jobs.

- Because of this, students struggle with or resist standard career center programming. YSN’s work addresses this specifically, with one of their goals being to reframe the conversation about work with young people. YSN’s flagship program, Exploring Your Potential (EYP), addresses students’ hopes, aspirations and challenges to help them craft career plans that make sense and get them excited, letting them take ownership and control of their own workforce path. Schools that have used EYP, such as Cal Poly and Cal State Bakersfield, are seeing 70-80% increases in confidence, clarity, focus, and direction across the board.

- Students also have little fluency about today’s new world of work, such as entrepreneurial options, the alternative economy, growth industries, global opportunities, how organizations are structured and thus what types of positions are available, and even how to get out and meet people in the field and present themselves as capable talent. Also profound is the fear and anxiety about what’s next after college

- The team behind EYP said one way they get students engaged in their own workforce readiness is to ask, “What problems do you want to solve in the world,” and then use that as a starting point to talk about critical skills and critical thinking development. “That concept of just wrapping [career planning] around something they’re so excited about and giving them that sense of self-efficacy that they can…impact change, and then [helping them] figure out how.”

What employers need vs. what’s being taught.

- Pietsch, who is also a father of three, shared his own experience coaching one of his sons as he ventured out to look for work. “He struggled with being able to articulate and relate his experience and skills in an interview. Far too many students don’t connect that they have experiences and skills that are valued by potential employers.”

- Pietsch stressed how important it is for schools to consider instituting programming through classes whenever possible. “Frankly, if it’s not for a grade students likely won’t do (the legwork) no matter how much you tell them it is good for them. Grades are a student’s currency, if you want an outcome where students are better prepared for a career, no matter the activity or skill, the best outcome is if it is for a grade.”

- Employers aren’t just looking for the “resume;” they’re looking for a culture fit. How to navigate that isn’t being taught.

- Academic policies that don’t translate to the real world—such as needing to take and pass Statistics to major in business—can result in students being told they can’t do something, which holds them back from their potential.

Preparing institutions to teach workforce readiness.

- From Sheridan “I really believe that for the broad swath of students, what we need is the ability for them to feel comfortable with conversations. …Sure, we’ll have the top scientific and tech students along the way, but it’s got to be more than that because they have to adjust to what the next technology is going to be. And…that’s a very difficult thing, frankly, for a tenure-track professor who’s been in a research mode to teach.”

- Instructors and institutions have to be willing and able to implement new programs and revamp how they teach. Octavia Brown, Director of Career Services at Pepperdine School of Public Policy, added how teachers, counselors, and institutions today need to be able to see where the jobs are going to be tomorrow.

- Hiring teachers/professors who understand today’s workforce is also a challenge. Krishna from RAND reminded all that the tenure system itself doesn’t allow for this, as professors have to research and publish and aren’t often there to teach. This is a deeper systemic issue to be addressed when it comes to workforce readiness. (Changing this isn’t easy! As Sheridan replied, “Well, you know, I’m in favor of world peace, too.”)

- So many industries now are new and emerging, and are therefore a perfect place for community colleges to focus their attention. The difficulty is that the data and statistics for these industries don’t exist yet, making it harder for 4- or 10-year institutions to quantitatively figure out what they should be teaching.

- The group agreed that more professional development and informational sessions like this one, talking about workforce and industry trends, would be most helpful and welcome.

The ominous skills gap.

- A big points of concern in this conversation was the skills gap, the gap between what employers need and what youth entering the workforce have been trained to do. Kumar pointed out that there are close to 7 million job openings currently, and every time the unemployment numbers come out, there are also close to 7 million unemployed. Clearly, those who are unemployed do not have the skills needed for the available jobs. Kushell contends that there’s also a big communication gap between employers and talent.

- The youth unemployment rate around the world is always two to three times higher than the general unemployment rate. In addition, as older workers retire, there aren’t enough trained youth to take their place, particularly in STEM careers. So the question becomes, how can we better prepare our youth?

- RAND studies have shown that the programs being offered in colleges are not matching the actual jobs available. Colleges need to be able to identify where jobs are, open the corresponding programs of study, and also guide interested students to those fields. This involves a major restructuring of how higher education currently works.

Too many college students? Not enough vocational training?

- From Kumar: “Every politician wants to send everyone to college, but suppose I get a degree in government and I’m going to work in a coffee shop, that is a mismatch. Are we short-changing our technical and vocational education?”

- The group discussed trying to expand vocational teaching, which gets passed over since states and school districts are held accountable to academic progress. However, vocational training would address some of the skills gap that is happening right now.

Next steps.

This conversation was a starting point. RAND and YSN look forward to hosting further collaborations with college administrators and other key stakeholders on the front lines of the student workforce preparedness pipeline. It is in everyone’s best interest that we collectively advocate for the introduction of more effective tools and frameworks for students…and administrators. The role of the educational sector in ensuring emerging talent is prepared and ready for the challenges ahead is now front and center. There are tremendous challenges, but this is also a most exciting opportunity.

More on RAND and YSN

For seventy years, RAND (www.rand.org) has been at the forefront of policy research and analysis in several areas, including education and labor markets. RAND is one of the founding partners of Solutions for Youth Employment (www.s4ye.org), which is a coalition of thought leaders working to solve the global problem of youth unemployment.

For twenty years, YSN (ysn.com), has been dedicated to inspiring young people to thrive in a way that is uniquely theirs—helping them figure out who they are, what skills they need to succeed, and how they can make an impact in the world.

Contact

Natalie Richards, RAND Corporation, Labor & Population nrichard@rand.org 310-393-0411 x6293

Jennifer Kushell, YSN/Exploring Your Potential.com jenniferk@exploringyourpotential.com 310-822-0261 x702